Monthly Archives: January 2017

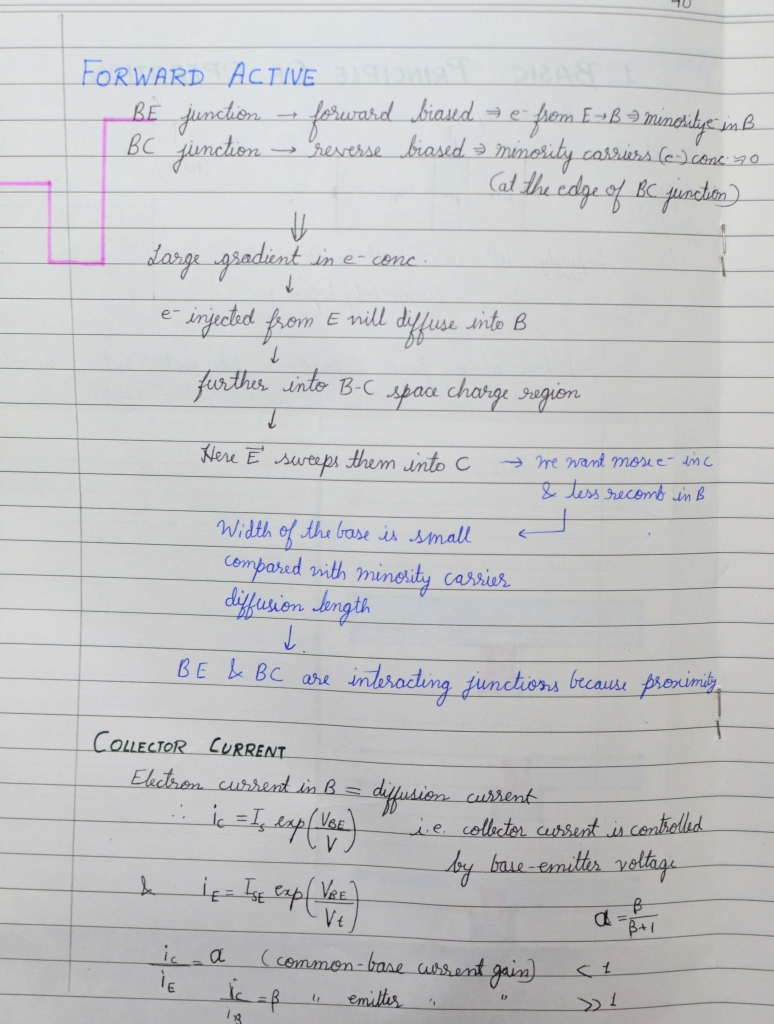

Semiconductors: BJT

Rigid Body

A system of particles in which the inter-particle distances rij are fixed and do not change in time. Hence, it retains its shape under the influence of external forces.

Another way to think about a rigid body is a system of particles under a force of constraint that keeps the distances between any pair of particles constant, thereby causing the system to retain its shape overall. This constraint can be thought of as a relation of the sort:

(ri–rj)2 = cij2

for any pair of particles i and j in the rigid body. It satisfies the criterion for holonomic constraint (cij is a constant). As a consequence, the internal potential of a rigid body is constant and the internal forces don’t do any work overall.

Semiconductors: Transistors

Kirchhoff’s laws

Kirchhoff’s laws are used to solve complicated electric circuits. Along with Ohm’s law, they are the first line of attack to solve any given circuit. However, bear in mind that these laws are valid only in the lumped matter discipline, i.e. when the circuit is in steady state.

Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law

The net potential drop across a loop is zero. In other words, if you end up where you started the sum of voltages along the loop must be zero.

The law derives from Faraday’s law of Induction which states that the voltage induced in a closed circuit is proportional to the rate of change of the magnetic flux it encloses:

Since we have a steady circuit, there is no changing magnetic flux. No changing magnetic flux means no net voltage (potential difference) induced in the loop:

Kirchhoff’s Current Law

The total current entering a junction is the same as the total current leaving it.

This law is basically a statement of conservation of charge because current is nothing but charges in motion and since there is no charge generation (or recombination) at the junction, it must be constant. More formally, this law derives from the Gauss’s Law:

Since charge is constant, ∂q/∂t = 0 and

If you are still confused, go watch this video by Crash Course Physics. By the way, all of their videos are great.

If you are really into Electric circuits and or Electronics, there is a series of courses by MIT on edx. The level is equivalent to the first semester in Electrical Engineering degree program.